Poplar Neck and the Prince George’s Slave Conspiracy

by Alan Virta, 1978

Statement of Significance

Two well-known authorities have tried to count the number of slave revolts and conspiracies that occurred during the 250 years of slavery. Both exclude individual acts of violence or individual escape attempts. Both count only instances in which arms were taken up by a number of slaves or some sort of violence committed in attempts to secure liberty, or, in the case of a conspiracy, plans made for such action. Herbert Aptheker counts both actual revolts, as well recorded conspiracies and lists 250. Winthrop Jordan limits his count to staged revolts and finds no more than a dozen. Aptheker required the participation of ten individuals to make a revolt or conspiracy; Jordan, twenty.

Clearly, then of the millions of men and women who endured slavery in America, only a very small percentage participated in a recorded conspiracy or rebellion. This is not to say that they might not have expressed discontent with their condition in other ways–it is to say only that participation in large scale movements was extremely limited. Of these movements, we know the identities of only a few of the participants. Jack Ransom is one. For this reason, his conspiracy and the Poplar Neck plantation should be noted.

The conspiracy at Poplar Neck is significant for a number of other reasons. From contemporary sources and the knowledge we have of the political and social climate of the time, we can identify several conditions which might have spurred Ransom to plan rebellion. His conspiracy is not one that can only be attributed to a general dissatisfaction with the state of enslavement. There were, in addition, several other known and possible contributing factors–the war with Spain and the other revolts of the time, the religious excitement of the day and Whitefield’s visit, and perhaps the widow Brooke’s difficulties–that might have led Ransom to think of rebellion.

The conspiracy has a local significance, too, because only one other major insurrection in Prince George’s County has been recorded by historians of slave revolts. That occurred in 1845, when slaves from Prince George’s County joined an armed march of slaves from other counties headed toward Pennsylvania and freedom.

Finally, although the Poplar Neck plantation has been divided into many parcels over the years, its location is still known. It is still a partly rural area. Driving a little off the main road into the woods, you can see the land of Poplar Neck as Jack Ransom might have once seen it. If only for this reason, proper note should be taken of Poplar Neck.

History of the Conspiracy

During the late 1730’s and early 1740’s, the British colonies in North America were beset by a succession of slave revolts and conspiracies. In September 1739, approximately eighty slaves engaged the local militia in a pitched battle near Stono, South Carolina. Less than a year later, a conspiracy was discovered in Charleston, and at least fifty slaves were hanged. During the Spring of 1741, Blacks burned several barns in Hackensack, New Jersey. Shortly thereafter, when military installations and other buildings were burned one night in New York City, slaves were blamed, tried, and executed. Maryland, too, experienced slave unrest, and according to local contemporary accounts, Prince George’s County escaped massive slave violence only because a conspiracy was discovered and suppressed before the revolt could be executed.

The revolt was planned in the plantations on the upper reaches of Piscataway Creek, approximately six miles southwest of Upper Marlboro, the county seat. The population of Prince George’s County in 1740 was approximately 17,000. Approximately 5,000 to 7,000, or thirty to forty percent of the total, were Black. Since the county’s borders in 1740 extended to the Pennsylvania border, and thus included vast areas of the rapidly growing, predominantly non-slaveholding Piedmont and back country, it is probable that in the Upper Marlboro area, one of the oldest sections of the county and one dominated by slaveholding tobacco planters, the percentage of Blacks in the population could have reached or exceeded fifty percent. Slaveholding families in the area, often outnumbered on their plantations by their slaves, had due cause for alarm whenever rumors of slave revolt spread.

The revolt was to have taken place in December of 1739. The leader of the conspiracy, as determined by the county court, was Jack Ransom, “a clever and sensible fellow between forty and fifty years old,” one of the several slaves of the widow Jane Brooke, mistress of the tobacco plantation Poplar Neck.

According to Stephen Bordley, who would later become one of Maryland’s foremost political leaders, and whom the historian John Thomas Scharf described as “one of the most prominent, wealthiest, and best educated in the colony,” the conspiracy had begun eight months before and involved two hundred slaves. Their plan was to meet on a Sunday afternoon (in violation of the 1725 statute prohibiting unsupervised meetings of slaves on the Sabbath), return home, then kill their masters’ families as soon as they had retired for the night, “except the young white women only, whom they intended to keep for their wives.”

After securing arms and horses from their plantations, they were to meet for a night ride to Annapolis, where they would divide into two parties and seize the power magazine and Council chambers. “When they had done (this) and sufficiently fortified themselves with arms and ammunition, they were to disperse in several bodies over the Town and Cutt the throats of Men, Women, and Children….”

Ransom then expecting the remaining slaves of the Western Shore to desert their plantation and hasten to Annapolis. From Annapolis he would launch attacks to kill the remaining whites. When the Western Shore had been taken, they would all return to Annapolis, divide up the houses, establish a government, and live like city gentlemen. If any army were raised on the Eastern Shore to oppose them, they would pack up everything worth carrying and flee with their young white wives to the back country. Bordley called the plot “as well laid as any of the kind that I ever heard of.”

Both weather and chance, however, prevented the uprising. Bordley relates that the Sunday originally set for the revolt was so rainy that most of the conspirators, including many of the leaders, failed to meet. Rain also disrupted the plans on December 1, the only specific date documented as being set for the revolt, and on at least one other following Sunday. In the meantime, however, a loyal slave of Henry Brooke, Jane’s son, discovered the plot and learned that his master was to be killed. He informed Brooke of the Plan. Brooke went to the authorities, several slaves were jailed, and the revolt, postponed three times because of rain, was permanently extinguished.

Six slaves were initially jailed, and several more were probably seized later. In January of 1740, John Hepburn and William Smith, justices of Prince George’s County, recorded the depositions of several slaves concerning the conspiracy. The depositions were taken to Annapolis and read before the Council on January 22. The Council recommended that a special Commission of Oyer and Terminer be established to try the slaves. A 1737 law entitled “A Supplementary Act to the Act entitled “An Act for the More Effectual Punishment of Negroes and Other Slaves…” however required that the slaves accused of conspiring or attempting to rebel be tried at county court. Therefore, Governor Samuel Ogle proclaimed that the slaves be jailed in Upper Marlboro until the next meeting of the county court and that the sheriff of Prince George’s County apprehend any other slaves suspected of being party to the plot. He further authorized the sheriff to “press such and so many persons as shall be necessary to attend and assist him….” The Prince George’s authorities did pursue their investigations, recording more slave depositions.

The trials were held at the March 1740 session of the Prince George’s County Court. Indictments were presented against five slaves – Jack Ransom; George, also a slave of Jane Brooke; Frank, a slave of Thomas Blanford; Peter, a slave of Richard Lee; and Will, a slave of Hyde Hoxton, all of Prince George’s County.

Jack Ransom, Frank, and George were charged with “Seditiously, Wickedly, Diabolically, and Horridly Contriving to Rebel and raise and insurrection within this Province of Maryland and to kill and murder a certain Jane Brooke, Henry Brooke, Joseph Brooke, and diverse others…to overthrow and Destroy the Government thereof and retain it by force and Arms.” All three pleaded not guilty. Ransom was convicted by a jury of twelve men and sentenced to be hanged. Frank and George were acquitted, as were Peter and Will, who were similarly charged but tried separately.

No other slaves were prosecuted. One slave, belonging to John Blanford, died in jail, and Mistress Brooke was compensated sixty pounds current money for the loss of Jack Ransom.

There is evidence to indicate that the extent of the conspiracy might have been exaggerated by men like Stephen Bordley and other Marylanders. Beside the five slaves prosecuted, Hepburn and Smith had bound only ten slaves to appear in court. That only five slaves were prosecuted and that the bills of indictment mention other “unknown” Negroes as participating in the plots indicate that the government could not identify the two hundred slaves claimed by Bordley to have participated in the conspiracy. Certainly the ten Blacks, who must have attended some of the meetings to learn of the plot, could have given the names of more conspirators to the justices if there had been very many more. The jury, too, could convict only Jack Ransom. Indeed, historian Jeffrey Brackett maintained that the conspiracy was nothing more than a “local excitement.”

Although the extent of the conspiracy might have been exaggerated, the reaction within the province indicates that the slaveholders were genuinely fearful of a slave uprising.

Two days after the depositions were read to the Council, Governor Ogle issued a proclamation ordering “all Officers as well as Civil and Military within this province… to be particularly careful in putting the several Laws in Execution to prevent the Tumultuous meeting of Slaves… and to Apprehend all such Slaves as shall be found

wandering who cannot give good and Satisfactory Account of themselves….” He further exhorted “all his Majestys’ subjects to be upon their guard and to prepare in the best and most Expeditious manner they can for the defense of themselves and their neighbours and for the better exacting and Obedience from the Civil Officers in the Execution of their Duty in the Premises.”

Local militia units were quickly formed. Bordley, in a letter to a friend, said, “the time is Come (alas this day which I never thought to see!) of being made a Soldier.” He boasted that within fifteen minutes his unit could muster forty armed horsemen and sixty armed foot soldiers. Arms and ammunition were distributed, and a guard watched the Council House and magazine every night in Annapolis. The Council, remembering that their throats were to be cut, advised that slaves not be allowed to enter Annapolis on Sundays without passes from their masters.

The wording of the court proceedings and an address by Governor Ogle also indicate genuine fear. Jack Ransom, Frank, and George were charged with “not having the fear of God before them but being moved and deduced by the instigation of the Devil.” Peter and Will were charged with “Voluntarily, Maliciously, Feloniously, Seditiously, and Traitorously” conspiring with Jack Ransom “against the Peace of the Lord Proprietary.” Ogle maintained that “if they had carried their Design into Execution, We should have been put to the cruel necessity of defending Our own Lives at the Expense of many of theirs, to the Entire Ruin of Numbers of particular Families, and perhaps of the Province in General.” Ogle, then, believed that the colony had escaped total destruction.

The conspiracy played a prominent part in the politics of the province a year later. The Governor wanted a tax levied to support the war against Spain, but the Lower House refused. He therefore tied the war measure to a bill to raise funds to defend the province against its slaves. The Upper House supported him, writing that “We should think ourselves too cool to the Publick Peace and Well being of the Province, if we were not heartily disposed to make further and better Provision, than at present, for Our common Security as well against rebellious Designs of Negroes, as hostile Attempts of His Majestys Enemies.”

The Lower House could not be convinced to support the tax bill, though. They felt that “it will be sufficient with the Arms already purchased and the Money in Bank, to enable us to defend Ourselves against Roman Catholics, Negroes, and any other Enemies…” It is significant that even though they would not appropriate more funds for defense, the Delegates classified their slaves as among their enemies.

What specific conditions, beyond general dissatisfaction with the state of slavery, might bring these slaves in Prince George’s County to plan a rebellion or make them think that one might succeed? Unfortunately, the answer is not documented in existing court records or Assembly proceedings, save for the charge that they were inspired by the Devil. Several possibilities, however, are suggested by social and political phenomena of the time and by Stephen Bordley’s letters.

Bordley relates that a slave woman, hearing Black men discussing the plot, related the story to her mistress.

“The lady did not believe her slave and did nothing to investigate her story. Bordley, then adds, “Foolish Woman! That sooner than give herself the trouble of looking into the affair aforesaid, she ran the hazard of having her throat cut; but perhaps she had a mind for a Black husband.”

Although he never explicitly states it, this woman without a husband almost certainly was Jane Brooke. Her husband, Clement Brooke, Sr., had been dead for two years and her children grown. Her will and her administrators’ accounts inicated that she possessed at least seven slaves, and that at her death her estate was valued at L638, making it an above average, prosperous plantation. Bordley suggests she did not take the time to properly investigate the charges, and perhaps Jack Ransom thought she could not manage the plantation or her slaves without her husband.

Perhaps, then this uncommon situation–that of a widow managing a plantation–led her slaves to entertain thoughts of rebellion.

The war with Spain, too, may have contributed to the causes of the uprising. The War of Jenkins’ Ear broke out in 1739 between England and Spain. News of the declaration as well as the tension which preceded it, created a climate of uncertainty in the colonies. There were rumors of Spanish invasion, Catholic plots, and French attacks from the West.

The governors sought to increase defense appropriations while the assemblies resisted, creating an intense political situation at home.

Historian Herbert Aptheker asserts that slaves were very much aware of current events and often planned uprisings in response to unsettling news. Perhaps the war and the uproar made Jack Ransom think a rebellion could be accomplished. The poor relations with Spain certainly influenced the slaves of Stono, South Carolina, to revolt earlier in 1739. The Governor of Spanish St. Augustine had proclaimed that runaways reaching his province would be free. The Stono rebels were marching to join the Spanish in Florida when they were intercepted by the militia.

Finally, the Great Awakening was occurring in the American colonies at precisely the same time the uprisings were breaking out. During 1739 and 1740 George Whitefield made a speaking tour through the colonies. In early December, he spoke in Annapolis and Upper Marlboro. The message of the Great Awakening was conveyed through emotionalism and “enthusiasm.”

It appealed to townspeople, the less-educated, and the back country farmers; it has been characterized as a “great democratic outpouring,” and the emotions generated “were to become an important and explosive element in the outlook on life of the eighteenth century…” Winthrop Jordan suggests that the Great Awakening was “suggestive of widespread heightening of diffuse social tensions throughout the colonies.” In the midst of these social tensions were those of the oppressed slave. The promises of the Great Awakening, particularly the condemnation of slavery by Whitefield, may have pushed the slaves to thoughts of rebellion. Rather than inspired by the Devil, as the bill of indictment against Jack Ransom proclaimed, the conspiracy might have been inspired by what the revivalist considered to be the word of God.

The Prince George’s slave conspiracy of 1739 never became an open revolt. No whites were killed. One Black was executed, and one Black died in jail. The excitement and terror caused by the plot subsided, and just sixteen months after it had been discovered, the Lower House could declare; “And notwithstanding the great Handle that has been made, and the Noise industriously spread over the province about our negroes, we must say, that from all the inquiry we have been able to make, we could never discover anything which might in any Manner be presumed to endanger the peace or Welfare of this Province, especially since the very few who had dared to think over any such Attempt, by the prudent care of the Government, have been already punished and suppressed.” [available free at Google Books – Archives of Maryland – Maryland Historical Society 1921]

Site Description (1978)

Poplar Neck plantation, the home of Jack Ransom, leader of the planned revolt, was granted to Major Thomas Brooke in 1671. It remained in Brooke’s hands until 1870, when Araminta Brooke sold it to Adam Diehl. Adam Diehl did not keep the plantation intact, but sold it in several pieces over the course of thirty years. The two largest tracts, 215 acres and 126 acres, were sold to Adam Diehl, Jr., and Nathan Diehl. In 1909 Adam Diehl, Jr. sold his 215 acres to G. Irene Tippett and it became part of the Tippett farm. Today the portion has been further subdivided.

The U.S. Navy maintains a right of way to the Naval Communications Station across the southern-most section, the National Rifle Association maintains a shooting range just north of that section and a housing development is located on another section. Nathan Diehl sold the remaining acreage in several smaller pieces to various individuals, most of them black.

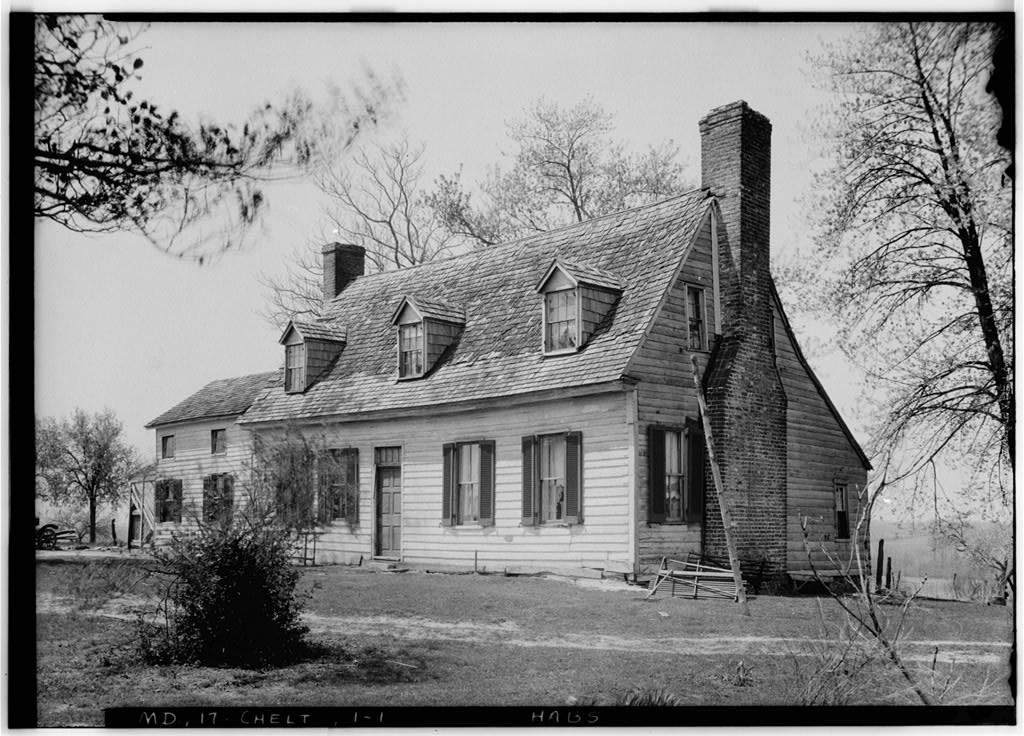

The Poplar Neck plantation house was located on the 126-acre portion sold to Nathan Diehl. It was in poor repair by the time the Historic American Buildings Survey (which listed It) in the 1930’s, and the Butlers destroyed it in 1947 to build a new home on the site. The Historic American Buildings Survey’s records dated the house from the late 18th century. However, historian James Wilfong believes the house recorded in the Historic American Buildings Survey is much older than HABS determines. He believes it is at least mid-18th century, and that it was built soon after the original grant in 1671. A photo of the house is contained in the Historic American Buildings Survey collection in the Library of Congress. (A copy of which is included in this study.)

Recommendation For Commemoration

(This section was written by Richard Miller for HUD)

The farm house of Jane Brooke, where Ransom was a slave is no longer extant. However, though greatly developed, there remain sections of the plantations which retain much of the flavor of the area where Jack Ransom roamed. Though probably not eligible for listing in the National Register of Historic Places, the site clearly meets criteria for commemoration by the state. Possibly a marker could be placed along Frank Tippett Road or some other thoroughfare where, passersby could gain an appreciation of the early Black presence in Prince George’s County.

Bibliography

Aptheker, Herbert. American Negro Slave Revolts, new ed. New York: International Publishers, 1974.

Archives of Maryland. Baltimore: Maryland Historical Society. Volumes 28, 40, 42. Containing Governors’ proclamations and acts of the Assembly.

Bordley, Stephen. Stephen Bordley Letter Book 1738-1740, a collection of his letters (MS.81.) At Maryland Historical Society, Baltimore.

Brackett, Jeffrey. The Negro in Maryland. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University,1889. Reprint ed., Free Port, N.Y.: Books for Libraries Press, 1969.

Jordan, Winthrop. White Over Black. Baltimore: Penguin Books, 1968.

Prince George’s County, Md. , Court Record (C1191). Liber X, ff. 573-576.

Savelle, Max. Seeds of Liberty. Seattle: University of Washington, 1948.

Whitefield, George. George Whitefield’s Journals (London: Henry J. Drane, 1905; reprint ed., Gainesville: Scholars Facsmiles and Reprints, 1969).

Wilfong, James C., Jr. “Poplar Neck.” Prince George’s Post. March 30, 1967.“

Wilfong, James C., Jr. “More on Poplar Neck.” Prince George’s Post. August 24, 1972.